Part 2: Linda Sams Executes a Perfect 10 in Aquaculture

This was a time when the provincial and federal governments understood the immense potential that laid in creating a steady supply of food, and in turn was very involved in the development of the industry

In 1982, most, if not all, women faced gender biases and challenges in the workplace, including pay inequality, harassment, lack of representation, stereotyping and bias, and limited career opportunities. Glass ceilings and gender-based promotion barriers prevented women from reaching their full potential in their careers.

Linda Sams, Sustainable Development Director, Cermaq Canada, not only confronted a windswept choppy ocean of opportunity, she also executed a Perfect 10 in her 35 years in the industry. She is a true pioneer and an inspiration for women in the aquaculture industry in Canada, and abroad.

To ride that new-industry wave, it required commitment in the face of difficulty, and utilising a combination of old and new knowledge, along with the ability to embrace innovation and progress.

In the late 1980s British Columbia was already seeing a decrease in the commercial fisheries in several areas, this was due to rapid growth and over expansion.

The aquaculture industry had already done its deep dive and staked its claim in Norway by the late 1980s. Word was spreading fast, and so naturally to entrepreneurial minds here in British Columbia, the province’s 15,985 miles of coastline seemed like an ideal place for salmon to grow.

“I don’t know if there was a rhyme or reason other than what people thought was suitable water, and probably there were already some interests from investments. I don’t think there were a lot of science behind the locations at that point. There were a couple areas that people were starting to explore the concept of ocean farming and they were looking at Pacific species originally, like coho, trout and chinook salmon predominantly.”

In the late 1970s and 1980s, the aquaculture industry in British Columbia would have exuded a charm in its simplicity, and its connection to nature. In these rugged coastal areas, there would have been a spattering of homesteading fish farms nestled in its picturesque coves and bays.

While the aquaculture industry was still in its early stages, there was an undeniable sense of pioneering spirit and optimism, so it attracted people of that ilk; Fishermen and divers, farmers, and trailblazing young biologists and scientists, all who were inspired by their deep connection to the ocean and the land. Here they sought innovative ways to cultivate healthy fish populations, with very little focus on sustainability.

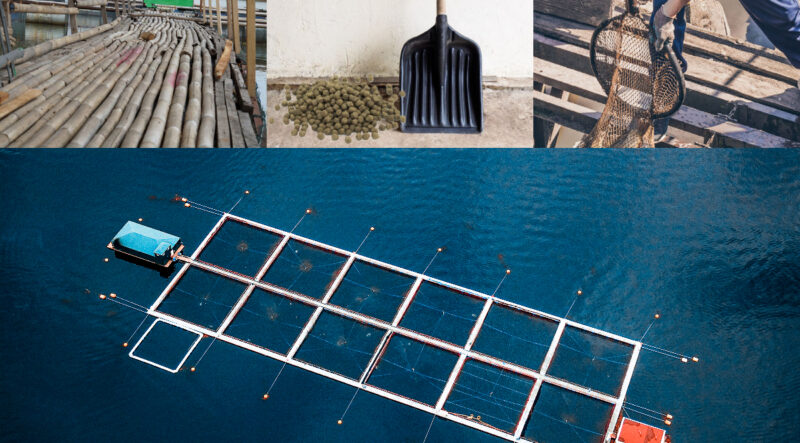

“They were experimenting with different nets and wooden cage systems…Being close to a hub, and to a road system and all that sort of thing was really front of mind, remember the type of equipment we had back then didn’t really lend itself to more exposed areas, so we worked in the more protected areas of Jervis Inlet and some of the channels in that area... At the same time, I believe, there was a start of the industry near Quadra Island and Campbell River, as well there were some established enhancement hatcheries that were being used for the first stock in the Sunshine Coast area.”

When one researches the history of fisheries and aquaculture in Canada, it reads like Game of Thrones on the high seas. There was always a power struggle to rule all and sundry. There was the rapid conglomeration of the commercial fishing industry, with a viral hiccup of international disputes, and there was the launch of government hatcheries, right behind many failed attempts at populating the waters with Atlantic salmon for sports fishing. And let us not forget the pre-UNDRIP contention with trampling on Indigenous rights in pursuit of their coastline.

And here was this new industry trying to float their ideas literally and figuratively, whose purpose was to try and get along with everyone so they could realise their entrepreneurial dreams.

“Where we were looking were in areas that were coastal communities that had long depended on resource-based industries, there was more development there, perhaps not the wild commercial fishing focus that you see in Alaska but there were development happening there. I think there was a real understanding of the market and what we could do to supply salmon to it in a very controlled and predictable way.”

This was a time when the provincial and federal governments understood the immense potential that laid in creating a steady supply of food, and in turn was very involved in the development of the industry. Pragmatic governments understood the importance of supporting another agricultural product that could create jobs and feed Canada’s population, and so they acted on it by supporting the industry throughout its infancy.

“Here was the state of BC versus Norway…I can tell you an incident that we had way back when. A Norwegian farm moved into the Bay across from a farm that I was working on, and they showed up with these amazing new systems. They showed up with the beginnings of the automatic feeding, meanwhile we were still feeding fish with snow shovels into wooden systems, and they had all this high Tech.”

Linda Sams worked in the industry from when it was the norm to grow fish in wooden baskets in close-to-shore operations, to the state of the art, leader-in-tech, sustainable, ocean operations that it is today.

Can you imagine the variety of maneuvers, the speed, the power, and the flow of Linda Sams trailblazing career in the aquaculture industry? In 35 short years she has seen more innovation, more technology invented, encountered more obstacles at every level of the industry and government, and formed strong lifelong relationships with Indigenous communities than any one person in aquaculture, female or not, to date.

From Farming Wild to Farming Mild

Atlantic salmon was first introduced as an aquaculture species on the east side of Vancouver Island. Its reputation as a fast-growing fish that was resistant to health issues, had more meat and less bone, and a low mortality rate that resulted in beautiful yields had a ripple effect in the budding industry. Here was a healthy salmon that was much more docile than its wild counterparts, Coho, and Chinook.

By the time Atlantic salmon arrived in British Columbia for the farming industry, they had been domesticated and selectively bred for quite a few generations in Norway and Scotland.

“It was like growing deer versus growing a Hereford. As a farmer, and I had to look at it through my farmer’s lenses, and we were pretty interested in what these Atlantic salmon were able to do and what a wonderful fish they were for farming. This was a natural move in my career, when you look at my actual education and what I had focused on, and for the fact that we were working in the ocean environment. We had to understand how we coexisted with the ocean from a farming perspective, but then also how we assimilated in that environment from an ecosystem perspective.”

In Canada, Linda Sams was introduced to the holistic-responsible approach to salmon farming through Scandinavian companies. These companies prioritised the social, environmental, and global aspects of their business, including concerns such as changing oceans, biodiversity, and climate change. This was in precise alignment with Linda’s academic background and her heartfelt commitment to farming. She was fascinated…

Tune in for Part Three on Saturday! Read Part One here.

Follow the link if you would like to listen to the entire conversation with Linda Sams, special guest on Salmon Farming Inside and Out Aquaculture Podcast.

The above podcast is hosted by the incomparable Ian Roberts, Director of Communications Mowi Canada, Scotland and Ireland, and Mari-Len De Guzman, Aquaculture Editor and Writer.

Image: screenshot of Linda Sams, Sustainable Development Director, Cermaq Canada